I inherited the Colorado Poets Center website in 2004. It started as a university-funded project at the University of Northern Colorado, hosted on their servers, built with Dreamweaver templates. At the time, that was the professional choice and what the university was using. Static site generators weren’t really a thing. WordPress existed but wasn’t an obvious fit since we were an .NET shop. Dreamweaver worked.

Over twenty years, the site grew to over 320 poets, 43 newsletters, and roughly 4,675 files. And for most of that time, Dreamweaver kept working. Not well, but well enough that the cost of migrating always felt higher than the cost of staying.

That changed.

Death by a thousand templates

Dreamweaver’s template system was the backbone of the site, and over two decades, it became the problem.

Every poet had their own template (in the early days 2 templates!). Every newsletter had one. There was a master template that everything inherited from, and then hundreds of child templates extending from it. Touching anything in the master felt risky because you could never be sure what would break downstream.

Even simple changes were painful. The site publishes a newsletter, The Colorado Poet, a few times a year. There’s a link to the current issue in the navigation. Updating that link, a task that should take a few seconds, meant waiting for Dreamweaver to reindex the entire site locally, then watching it churn through every dependent template, and then SFTP-ing hundreds of files to the server. For one link.

Yes, I could have used includes, but at that point in time, Dreamweaver did not handle .asp includes well.

Creating a new poet page meant duplicating a template, manually setting up the folder structure, adding images, and making sure everything wired up correctly. It was doable, but it was slow, and it was fragile.

None of this was catastrophic on any given day. But over years, the friction compounds. You start dreading changes instead of making them.

The €948/year wake-up call

I’d thought about migrating before. Every couple of years, I’d look at the effort involved and decide it wasn’t worth it. The site worked. I knew its quirks. And there were always more interesting things to do.

Then Adobe sent me an email: the Dreamweaver subscription was going up to €79 a month. That’s almost a grand a year for a tool that hadn’t meaningfully evolved in years, running a workflow that made me dread simple updates.

At the same time, I was already using GitHub and CI/CD for deployments, which just highlighted how outdated the rest of the setup was. I had a small PHP/MySQL section for news updates that wasn’t used anymore. I was maintaining a MySQL database just to store a list of poets and their metadata, something that could easily live in Markdown or YAML.

The balance finally tipped. The cost of staying was now clearly higher than the cost of leaving.

Why Hugo

I didn’t evaluate a bunch of static site generators, if I did, I’d still be evaluating. I’d used Jekyll for this site and have found it clunky. Hugo had a reputation for handling large sites well, and this site is large.

What I actually cared about was whether Hugo could answer these questions:

- Can it handle thousands of pages with the nested architecture?

- Can I generate an A–Z index of all poets automatically?

- Can poets be listed by city automatically?

- Can newsletter issues link to the poets they feature?

If yes, then the rest was implementation detail. Hugo’s taxonomy and list systems handled all four. That was enough.

AI made this migration possible

I want to be honest here, without AI, I probably wouldn’t have done this migration. The site had been in Dreamweaver for twenty years precisely because the conversion work felt overwhelming. Hundreds of poet pages with inconsistent structures. Twenty years of accumulated decisions and tech debt.

Here’s how the actual conversion worked.

Step 1: Strip out the Dreamweaver comments

First, I edited the master template and stripped out everything that was repeated on every page. Next, I used the find-and-replace to remove the template markup, comments, and repeated code that still existed. This gave me stripped-down HTML files — just the content, no layout scaffolding.

Step 2: Generate Hugo index files with AI

Each poet in Hugo needs an _index.md file with the right frontmatter — name, location, metadata, list of poems, and a reference to their content. I fed the poet’s info to Claude and had it generate these index files. One by one, 320+ times.

This is the part that would have killed the project without AI. Writing a script to parse twenty years of inconsistent HTML and extract the right metadata would have been its own project. Having AI look at each poet’s existing page and produce a clean, structured index file turned weeks of tedious work into something manageable.

Step 3: Move the content

The existing HTML files moved mostly as-is. This included the actual poems, bios, and essays that had been edited over the years. I wrote a shell script to copy the files from the old directory to the new one as is. Hugo serves HTML content files just fine. I didn’t need to convert everything to Markdown. Then a quick smoke test to make sure it appeared correct.

Step 4: Build the Hugo templates

This was the straightforward part. A base layout, a poet list template, a single poet template, newsletter templates. Hugo’s templating is simple once you understand the lookup order. And honestly, I asked a lot of questions to Claude in the beginning!

The grind

I’m not going to pretend this was fun the whole way through.

The site had twenty years of accumulated file organization decisions. Early on, poet images lived in a single shared poet_images folder. Later, I started putting images into individual poet folders. So the site had both patterns, and I had to normalize that.

Even with automation and AI, there was a long middle stretch of repetitive, monotonous work: moving files, checking output, fixing edge cases, quick tests. That’s the reality of any large migration, and anyone who tells you otherwise is either lying or has never done one.

What 4,675 files looks like in Hugo

The site now deploys from a GitHub repository. Changes go through CI/CD. The build takes seconds and the deployment a few seconds more.

Adding a new poet means creating a folder, dropping in an _index.md with the right frontmatter, and adding their content files. No template duplication. No reindexing. No SFTP.

The A–Z poet index, the location-based listings, the newsletter cross-references are all generated automatically by Hugo at build time. These are things I maintained manually for years. Now they just work.

Editing the site in VS Code feels normal. For quick fixes, I can use the GitHub mobile app from my phone. The entire workflow went from “boot up Dreamweaver, wait, pray, publish” to “edit, commit, done.”

And there’s no Adobe subscription anymore.

Was it worth it?

Yes. It took longer than I expected, which I was expecting, but still. The site went from something I dreaded touching to something I can maintain without friction. For a site that’s been around for twenty years and serves a real community, that matters.

If you’re sitting on a legacy site and thinking about migrating, here’s what I’d tell you: the reason you haven’t done it yet is probably the same reason I waited, the work feels overwhelming. AI changed that equation for me. It didn’t eliminate the work, but it made the most tedious parts tractable. That was enough to tip the balance.

The Colorado Poets Center is still online, still growing, and now running on a stack that doesn’t make me wince every time someone asks me to add a poet.

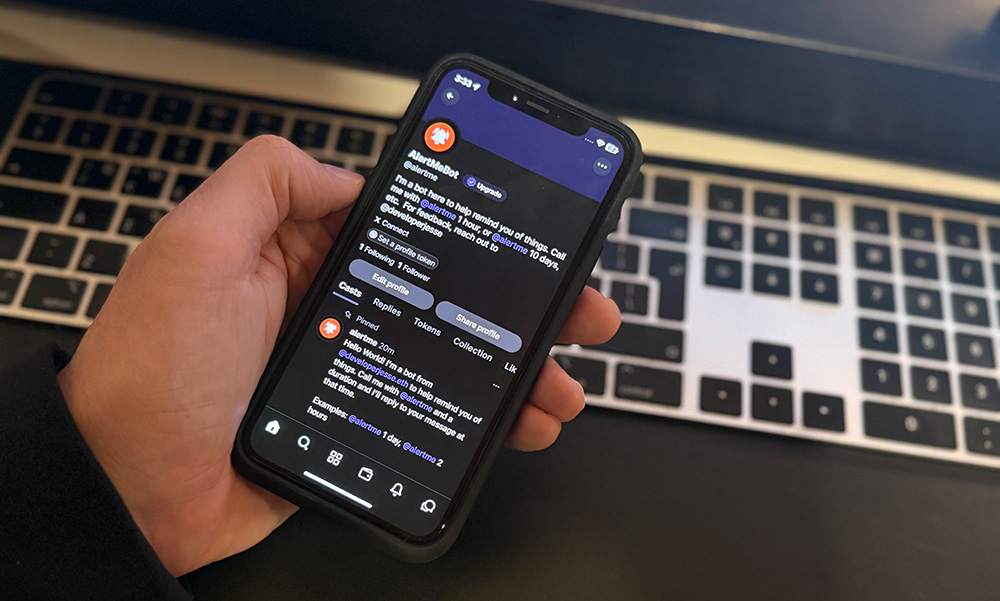

AlertMe - Farcaster Reminder Bot

AlertMe - Farcaster Reminder Bot

A Developer's Guide to Storytelling

How to make your technical work matter to people who don't speak code

A Developer's Guide to Storytelling

How to make your technical work matter to people who don't speak code

Let them fix it!

Let them fix it!